Danial Nord's experimental mixed-media installations, videos, and sound pieces are vivid, boisterous and, as he puts it, "wave their aesthetic arms in the air." With his carnivalesque artworks, he appeals to diverse audiences by consciously seeking to entertain them. Nord utilizes media conventions of popular culture, for he believes it is from a place of instant accessibility and familiarity that audiences will be more receptive to his message. His goal is to prompt viewers to engage in a more analytic mode of thought about the imbrications of consumer culture with technology, the trespass of media into our domestic lives and personal identities, the environmental repercussions of our insatiable desire for newer-faster-cooler gadgets, and even our status as a nation when the sociopolitical and economic might of the United States is now on the wane.

For his COLA project, Nord repurposes Mickey Mouse as a vessel to carry his message. This iconic, reified, and quintessentially American cartoon character is to him an "easy symbol." Mickey has been everywhere and done everything. He has posed with every US president since Truman and has participated in American war propaganda. From the cheery pop of Roy Lichtenstein to the bilious postmodern parables of Llyn Foulkes, many artists have appropriated Mickey's features to comment on our culture. And yet, populist Mickey does not belong entirely to us, as indicated by the famously heavy-handed lawsuits brought by the Disney Corporation to protect their beloved trademark from being knocked off.

The rodent's ubiquity is just as Walt Disney would have it. From the earliest days of Disney's enterprise, Mickey Mouse images and toys were inserted into Hollywood publicity stills and newsreels. Disney clearly "got" product placement and celebrity endorsement, perhaps learning from the early success of cartoonists like Richard Outcault and his lucrative "Buster Brown" franchise. By 1929, Disney had licensed Mickey's likeness, an action that would provide an important revenue stream for his animation studio. Right away, Mickey was slapped onto everything from spiral school notebooks and wristwatches to children's clothing. In this respect, Mickey's last name might as well have been "Merch."

Fate Machine, 2008

Fate Machine, 2008Weimar-era German philosophers Theodor Adorno and Walter Benjamin argued heatedly about the societal implications of Mickey Mouse for the working class. In a handwritten first draft of his seminal essay, "The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility," Benjamin included a section entitled "Micky-Maus," calling the animated character a "figure of the collective dream." Benjamin believed slapstick films and cartoons might provide "psychic inoculation" to counter volatile social tensions brought about by technification. In his estimation, the "forced articulation of sadistic fantasies or masochistic delusion" depicted in such films would prevent a "dangerous ripening of the masses." Collective laughter signified for Benjamin a "premature and therapeutic eruption of mass psychoses." Adorno scoffed at the ameliorative potential of collective laughter for cinema audiences. In 1936, he complained it was not "good and revolutionary" but rather filled with the worst "bourgeois sadism." The release of such laughter was nothing more than Schadenfreude. Whether persuaded by Adorno's argument or incapable any longer of sheltering his concepts against the rising tide of mass violence in Nazi Germany, by the final version of his text, Benjamin's references to Micky-Maus and the "therapeutic eruption" of laughter had disappeared.

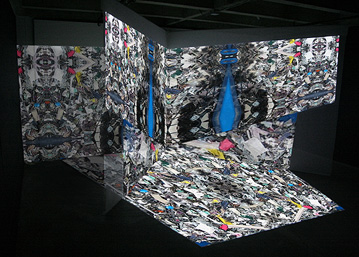

Monument, 2009

Monument, 2009 The encroachment of popular culture and merchandizing into all realms of society has essentially been unstoppable. Our ambivalence towards this aspect of contemporary life still bears all the markers of the debate between Benjamin and Adorno seventy-five years earlier. In recent works, Danial Nord addresses consumer culture in ways that give voice to the anxious question, "Who is consuming and who is being consumed?" In his video installation Fate Machine (2008), cast-off computer components are drawn into the frighteningly beautiful maw of a giant mechanical shredder, where they are reduced by violence to toxic, post-technological mulch. In Monument (2009), Nord's large-scale, multimedia fare-thee-well, a stack of forty obsolescent analogue televisions salvaged from the dump plays the final moments and swelling soundtracks from hundreds of bygone Hollywood films. With both Fate Machine and Monument, the viewer is asked to consider how every technological advancement is attended by tremendous loss and waste.

Target, 2010

Target, 2010 But the products just keep coming. In Target (2010), Nord presents covert video shot in the superstore of the same name. Pushing the familiar red carts, shoppers with children following in their wake peruse endless rows of consumer products arranged to stimulate impulse buying, another variation on the therapeutic eruption. In its final form, Nord's digitally manipulated video resembles a brightly colored kaleidoscope. Closer inspection reveals that everything is bent to conform to the bulls-eye shape of the corporate logo.

In Danial Nord's current rendition of Mickey Mouse for the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery, the massive sculptural figure derives its shape from the black plastic backs of discarded televisions he has scavenged and pieced together as a carapace. The icon's position on the floor calls to mind both the latent social aggression of early Disney animation and the vulnerable fetal pose of a homeless man passed out on a sidewalk after a bender. No doubt, this Mickey is a goner. Excessive consumption is hard on our humanity. Into the darkened room, from Mickey's core, emanates a radiant montage of television broadcasts. It is as if Mickey's life force streams as light from every slit and fissure in the plastic. In many spiritual and philosophical traditions, light is a metaphoric corollary of truth. Here, light serves also as a countermand. It breaks us out of the hypnotic trance induced by mediated spectacle. It asks us for a moment of empathy as we contemplate what we have lost.

All quotes from the passage about Benjamin and Adorno are drawn from Miriam Hansen's "Of Mice and Ducks: Benjamin and Adorno on Disney," South Atlantic Quarterly 92:1 (Winter 1993).

—Kristina Newhouse