Mark Dean Veca and I met in the late 1980s, when he was a recent Otis graduate

and I a recent CalArts dropout, both of us working in art galleries installing exhibitions,

crating, shipping and doing administrative work. Veca was burning out on the

autobiographical paintings and drawings of what he called "really banal situations" that

had been his focus for the past five years or so. We were in-between somethings, in need

of a shake-up, new states of mind, overhauls of indistinct parameters.

As I recall, the Veca overhaul closely followed the election of George Herbert

Walker Bush. We'd been sitting in Veca's studio that vile early November afternoon in

1988, sullenly watching election results on television and drinking too much coffee. By

late afternoon the networks called the election for Bush, and Veca and I switched from

too much coffee in his studio to not enough martinis at Musso & Frank.

Then there was a dull blur, then Veca started making furniture and moved to

New York, and we fell out of touch.

When I accidentally rediscovered Veca in the late 1990s, I remember feeling this

profound sense of hope and a kind of joy that I don't feel often: He'd gone through

something and emerged with a magical formula that felt true, that was his and his alone.

Some call it finding a voice: a natural change that can't be forced but must be

pursued, or at least nudged; following a path that feels intimate and organic. For Veca,

the path forward led backward, to inspiration from his childhood and the fundamental

urge to draw. As a small Veca growing up in Livermore, California, about an hour's drive

east of San Francisco, Mark Dean learned the pleasures of drawing by copying images

from "Mad" magazine, especially the work of Don Martin and Mort Drucker. Then, in

high school in the late '70s, he got into the underground comics that were being created

at Last Gasp and Rip Off Press, just across the bay. He'd drive to a comic-book store in

nearby Berkeley and pick up the latest work of Bill Griffith, Gilbert Shelton and Dave

Sheridan - "Zippy the Pinhead," "The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers" and others -

then drive home, study and draw. He knew, even then, that somehow drawing would be

a big part of his life.

Turns out the furniture-making in New York had led to candle-making, which

led, amazingly enough, to money, which led to lots of studio time, the fruits of which led

Veca to attract the attention of The Drawing Center's director, Ann Philbin (currently

director of the Hammer Museum) who invited him to create a temporary mural on the

gallery wall in 1996. Having studied the mechanics of mural-making with Kent Twitchell

at Otis Art Institute, Veca jumped right in, and this was the beginning of what would

become a period of profound large-scale painting and drawing of breathtaking

installations jam-packed with fantastical, frenzied interplay of pop and historic icons of

all ages, pulsing together in unsettling, electrifying patterns.

Now, the Veca I'd known in the late '80s was a great draftsman and had a fine

comedic mind, but when images of his new work came across my desk in the late '90s --

holy !##@!! I didn't know he could do that, these pulsing, vascular, living, breathing

maelstroms of comix-style psychedelia: simple black lines so exquisitely, gleefully,

fiendishly and precisely rendered, bursting forth in high contrast from intense fields of

color.

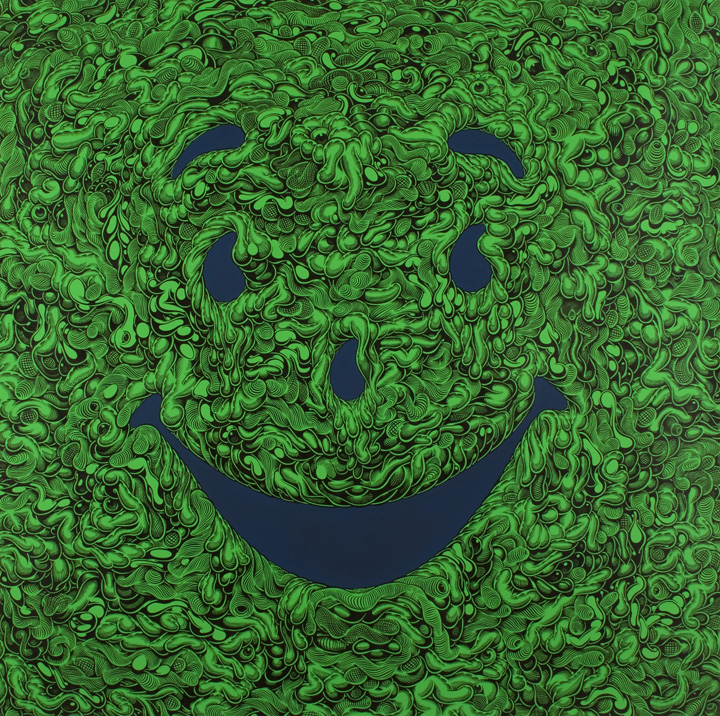

And the voice of Veca gets stronger and stronger, recently crucifying '70s

corporate food iconography by depicting the icons in states of decadence and putrefaction,

heightened by the artist's tongue-in-cheek choices of background colors: the vermillion

used in "Sorry Charlie (Vermillion)," 2011 is a pigment originally derived from mercury,

the poison now commonly found in tuna. Similarly, Veca chose an industrial-waste green

background for the Kool-Aid Man in "Oh Yeah," 2011 and an amber (alert!)

background for Tony the Tiger in "Great," 2011.

So far, the site-specific mural-based installations that Veca's made have been

painted over after the exhibit ends, to become artifacts concealed in the galleries' walls.

But finally, this August, Veca will be executing his first permanent public art project, in

Lower Manhattan, in the cafeteria of a public school that occupies the bottom five floors

of 8 Spruce Street, an otherwise residential tower designed by Frank Gehry -- which

means that among the hundreds of children eating lunch at the adjacent tables, there'll be

a handful who'll see Veca's work and whip out their drawing pads, and the wondrous

cycle will continue.

—Dave Shulman